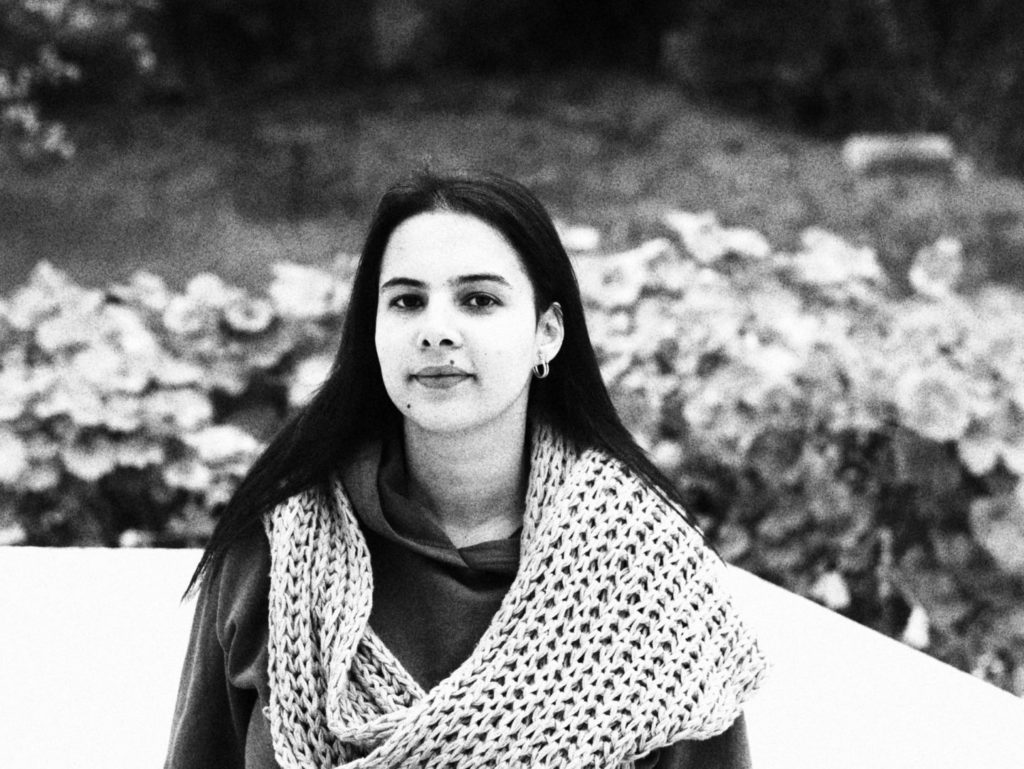

Does Tunisian folk dance, rich in its many facets, play a role of memory and transmission in this performance? How can dance both preserve and reinvent ancient traditions, particularly those linked to the role of women in Tunisian society?

Rochdi: I have been working on Tunisian folk dances since 2011, the year of the revolution. These dances convey an aesthetic and a symbolism deeply linked to daily life in Tunisia. They are the bearers of memory, and vectors of cultural transmission within society itself. Through them, a form of Tunisian identity or uniqueness emerges in this performative work. By exploring dances such as Fazani, Jelwa and Bounaouara, I wanted to question the relationship between contemporaneity and the popular dimension of these practices. Taking these dances out of their social and cultural contexts to place them on an experimental stage is a delicate gesture: the risk is always to deprive them of their symbolic and historical charge. Preserving while reinventing was the objective of this project, which began fourteen years ago. The work also explores gender relations and the tensions between femininity and masculinity in dance. So-called feminine dances are performed by a male body, and vice versa. This inversion of roles and blurring of the boundaries between feminine and masculine creates a kind of vertigo. The female dances I chose for this performance are linked to nuptial ritual and the celebration of fertility. Through them, I sought to mobilize and articulate parts of the body traditionally connoted as feminine – the belly, the pelvis, the hands – while using objects, accessories and costumes that accentuate the feminization of the male body’s movement.