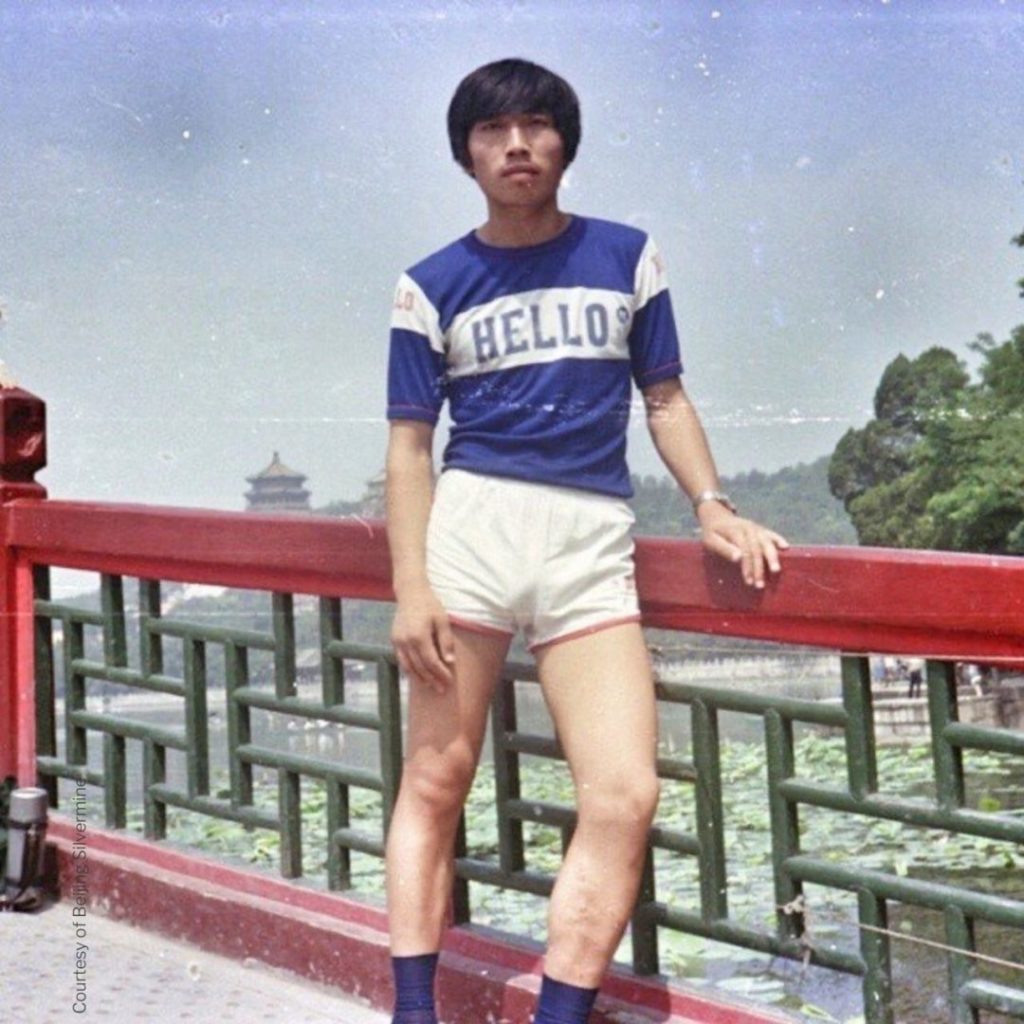

DoorZine: Dong plays on the porosity between three layers of representation of the Three Gorges: documentary film, fiction film, and painting. Han Sanming links the three, as he also appears in Liu Xiaodong’s paintings. Why this permeability between three modes of representation of the same subject?

Han Sanming is my cousin, and he is a real miner. I find him extremely convincing on screen. He first appeared in my films in Platform, then in The World and Still Life. He always plays silent characters, because in real life he doesn’t like to talk much. However, without saying a word, his character reveals many aspects of his life. For me, Han Sanming represents a large category of individuals. They are not just migrant workers, nor those we call honest people; they are what I call the millions of Chinese people who have no rights. Like the right to tell their own story.

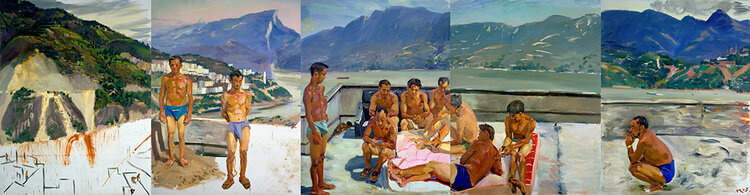

DoorZine: At the end of Dong, Liu Xiaodong says about his series and the fate of the people and landscapes disrupted by the Three Gorges Dam project: “It’s ridiculous to think that art can change things. (…) As long as I live, I will try to express my point of view. I represent them by painting their bodies and expressing some of my ideas. But I also hope that my painting restores the dignity that every human being possesses.” You have made two films on the same subject. By winning the Golden Lion in Venice in 2006, Still Life brought the Three Gorges Dam project and its consequences for individuals, particularly Chinese workers, to the attention of the Western world. Do you think cinema can change things?

I have always believed that cinema, as an element of culture, could hardly bring about concrete change in people and society in the short term. But our society, in order to open up and progress, relies mainly on cultural changes. I am thinking, for example, of the May Fourth Movement*, which arose primarily from a reform of the Chinese language, from an evolution from classical literary writing to modern vernacular writing. The impact of such a cultural change on China is still felt today. We filmmakers must not exaggerate the importance of our work, but we must firmly believe in the power of culture.