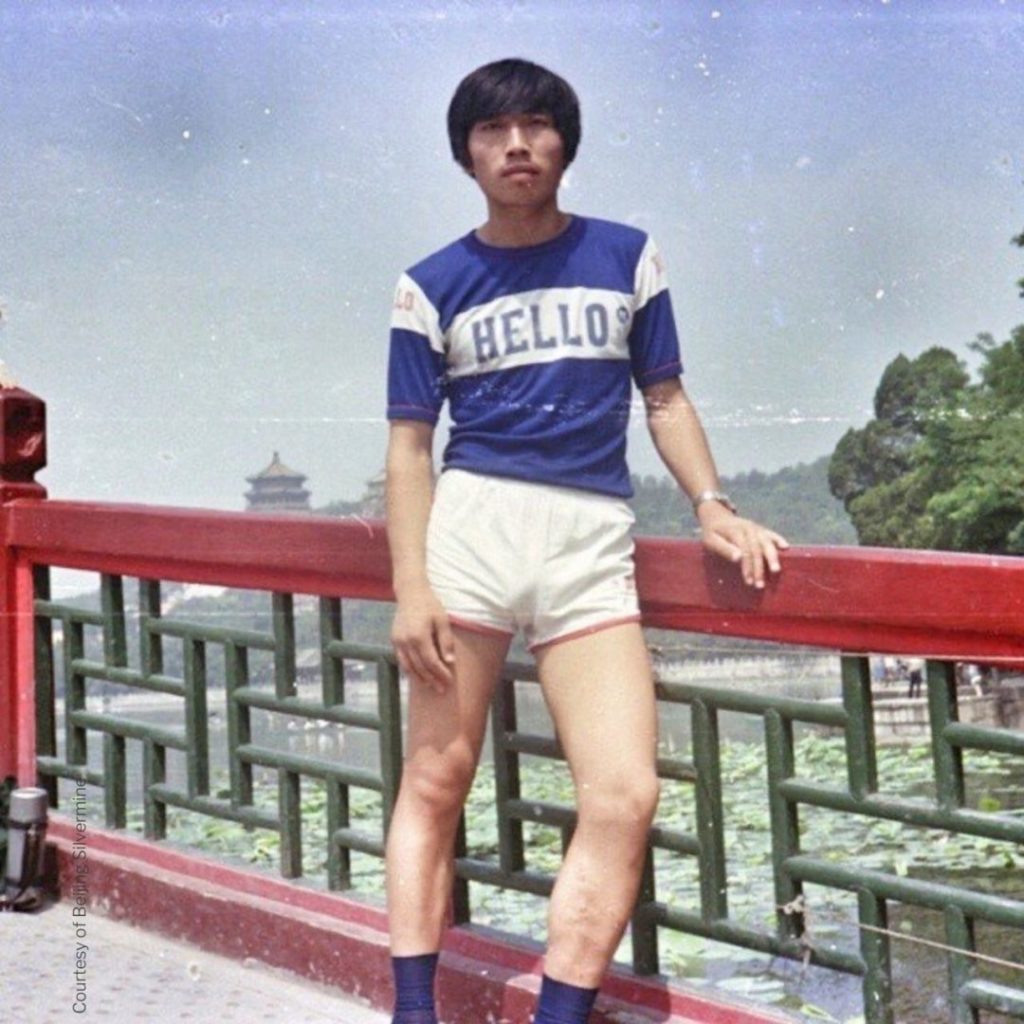

Since the vocabulary of brushwork that shapes Chinese painting is inspired by nature, it should be possible to find it directly in nature, hidden in its details. Some projects are undertaken simply because the qualities of a particular geography evoke classical painting; others because a specific subject has been an important theme in classical art. Inevitably, however, the strongest works combine both aspects.For the series Map of Mountains and Seas, I was inspired by writer Rebecca Solnit**:

“The world is so completely made that it requires not more making, but rather the opening of a crack to return to the origins of its process. ‘Unmaking’ is the primary metaphor and ‘backward’ the most meaningful direction: the act of creation then consists in undoing, in recovering the original rather than increasing the new.”

Map of Mountains and Seas is a photographic reflection on the Classic of Mountains and Seas, a text whose oldest version dates back to the 4th century BCE. The Classic of Mountains and Seas stands at the confluence of real and abstract geographies. Hundreds of mountains and rivers are mentioned, yet only a few of these places correspond to actually identifiable sites. Between these real locations stretch vast imaginary spaces, along with descriptions of flora, fauna, medicinal herbs, and the mythical creatures that inhabit them. Each photograph is a map, regardless of its degree of abstraction or precision in relation to the broader context of the world around it. Once the photographs in the Map of Mountains and Seas series are mounted, I inscribe the GPS coordinates and the azimuth (degrees from north***) on the margin or in the caption of the work. If you stand at that exact point on the globe and look in that direction, you will see this place—but beyond that, there is no further categorization.

The Taoist scholar Guo Pu**** wrote in the 4th century in his commentary on the Classic of Mountains and Seas:

“Contemporary readers regard the Classic of Mountains and Seas with suspicion because of its exaggerations, its absurd and extravagant assertions, and its strange and fanciful expressions. I have often debated this by quoting Master Zhuang (Zhuangzi*****):

‘What people know is less than what they do not know.’

This is precisely what I have observed in the Classic. Thus, who can claim to give a complete description of the immensity of the universe, the abundant forms of life, the benevolent sustenance of yin and yang, the countless distinctions between things, the mingling of essences that overflow and clash, the wandering spirits and strange divinities that take form, migrate toward mountains and rivers, and adopt the beautiful appearance of trees and rocks? Yet,

Harmonizing their distinct tendencies,

They resonate like a single echo;

Perfecting their transformations,

They merge into one image.

Some call things ‘strange’ without knowing why they name them so; they call things ‘familiar’ without knowing why either. What is the reason? A thing is not strange in itself; making it strange depends on me.”

Guo Pu 郭璞