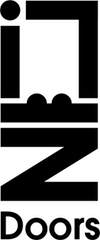

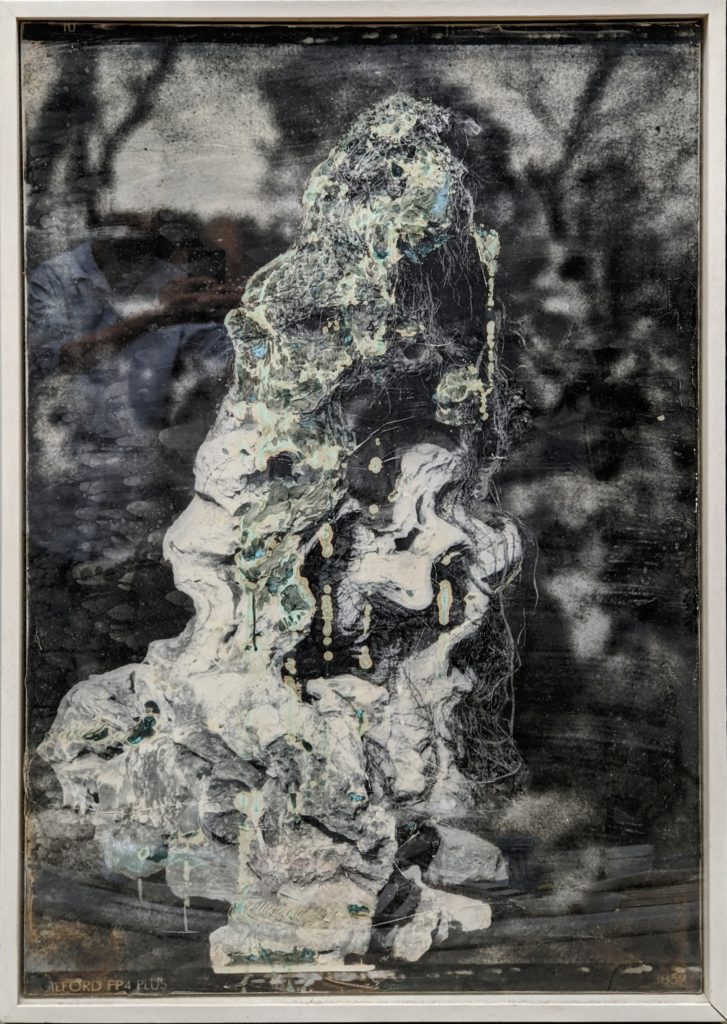

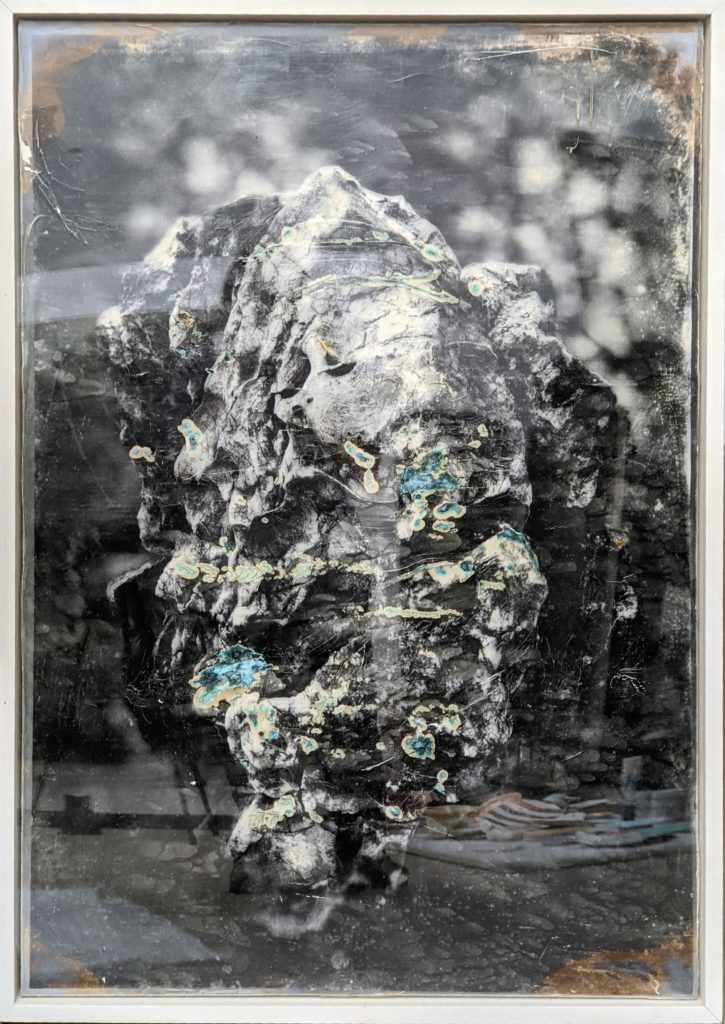

The work of the artist Noémie Goudal (born in 1984) makes real and theoretical geographies co-exist, creating a space somewhere between physical reality and mental representation. Since the beginning, the artist has been interested in the links between optics and perception, observation and interpretation, science and art. After her three series that explored the theoretical systems of the sky (Observatories, Towers and Southern Light Stations), Noémie Goudal begins in 2017 a new body of work about the history of science and the theories of Earth’s formation (Telluris, Uprisings and Dismantlings). Originally inspired by ancient discoveries which revealed the presence of fossils on mountains tops, the series Soulèvements (Uprisings) (2018) is an interpretation of centuries-old observations of these fossils. Soulèvements underlines the absurdity of such an undertaking.

“A first glance at these photographs and we see mountainous rock formations. A second and it becomes clear, from the fine grids of light that shine through the formations like crevasses, and from their often wildly irregular edges, that the rocks were never in fact there at all. To create this illusion, Goudal fixed a stack of around twenty mirrors around each rock at different angles, then photographed this ‘edifice’ so that we see in the resulting image the many reflections of the rock’s surfaces as one. Her constructions symbolise the great uplifts that create mountain ranges, but they also suggest the intellectual revolutions that can shatter the status quo and change a field of knowledge beyond recognition. Slippery to behold, they are a reminder that everything we believe to be true can be turned on its head in a minute.” (Emma Lewis, preface to the book Soulèvements published in 2020 by RVB Books).

What better tool can illustrate this complex feat than a camera? From the beginning, its importance lies not only in what it reproduces, but in what it is capable of producing within the spectator’s mind. Did Arago not see in the daguerreotype both a means of mapping territories and a kind of artificial eye capable of making visible atmospheric matter and celestial bodies?