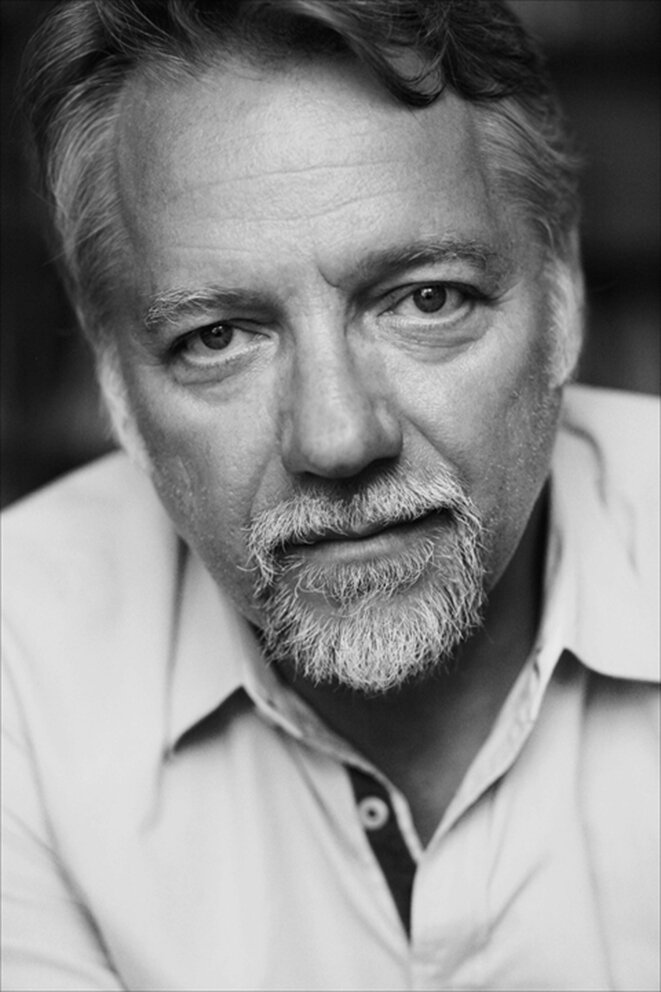

DoorZine: Since the 1980s, your work has focused on nature as it is transformed by industry. Your approach is global: you have carried out projects in North America, India, Bangladesh, Asia, Australia, Europe, and Russia. In the book and documentary Manufactured Landscapes (2003 and 2006), you examine the effects of industrialization on the environment, allowing the public to understand the origins of the consumer goods they use daily as well as the scale of the landscape transformations resulting from our pursuit of progress. You have said that your project is a way of “looking at the industrial landscape as a way of defining who we are and our relationship to the planet.”

What place do your series made in China—particularly those on the site of the Three Gorges Dam—hold within the broader context of your work?

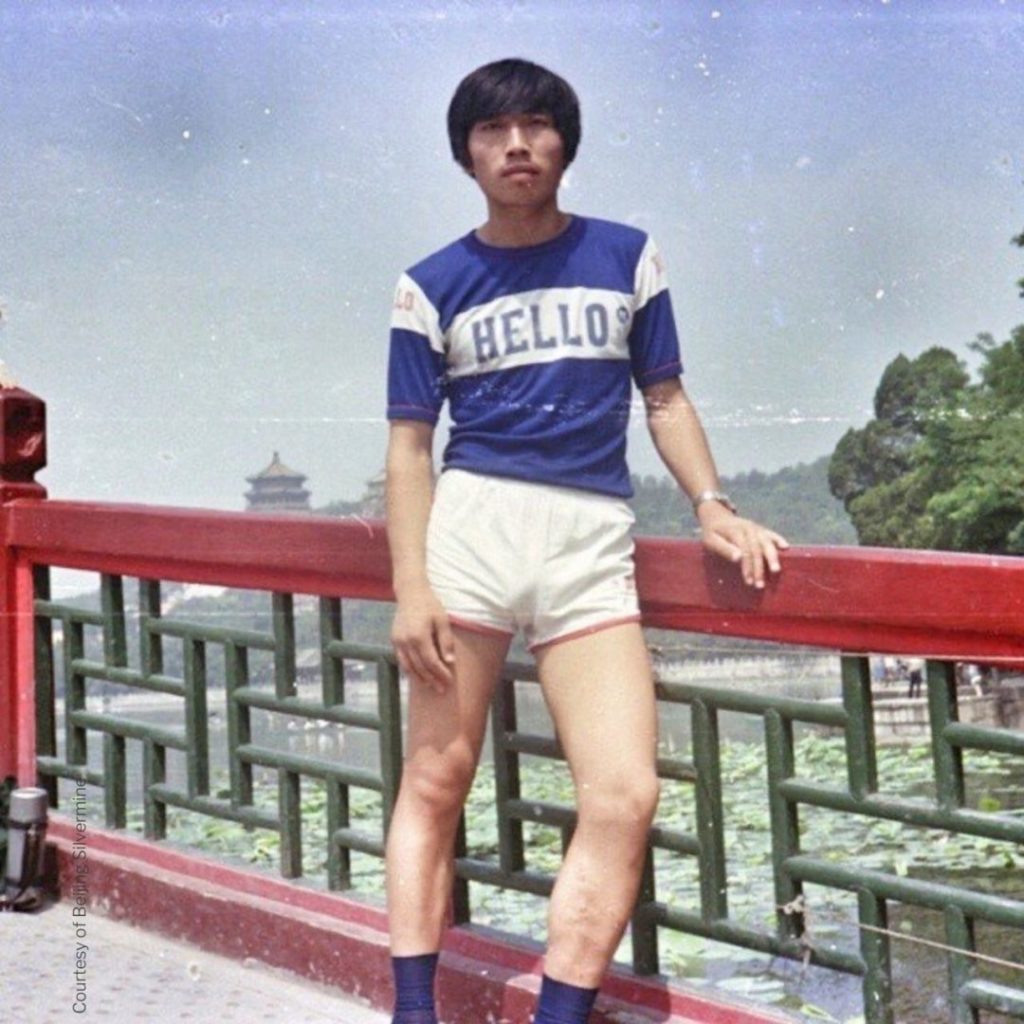

Edward Burtynsky: My work in China was produced at a time when the Chinese industrial “machine” was accelerating and providing inexpensive products to the entire world. For me, this was a very clear sign of how the twenty-first century was beginning to unfold. Considering the massive and constantly expanding size of the global market, I turned my attention to China to observe the enormous scale of the industrial systems the country was developing, with a particular interest in resource extraction, the manufacturing and transport of huge quantities of goods, and the recycling of waste from around the world—all on an unprecedented scale.

DoorZine: In this series, your images show destruction, construction, and the transformation of the landscape more than the fate of the people whose lives have been affected by the dam. Human beings are almost absent from your photographs. Why is that?

That is not entirely accurate. There are many images in my Three Gorges series that include people. But with regard to the images in which people are not the central focus, I was more concerned with the manifestation of human presence and with the way human hands transform the landscape on a colossal scale—an extension of the conceptual project that drives my entire photographic practice. I am most interested in humanity through the expression of large-scale industrial “systems”—the damage inflicted on the planet by human beings in order to achieve growth and progress at any cost.

DoorZine: You emphasize that your work is neither a glorification nor a critique of industry. By creating beautiful and striking images, you aim to make the public aware of the impact of their way of life on the environment and to raise awareness about the consequences of human action on the landscape. What, for you, is the function of art and photography?

For me, the function of art is to awaken consciousness… to provide new information, to help people think about what they see from practical, spiritual, and aesthetic perspectives. In my case, it is about the potential consequences of our greedy actions on the planet. It is very important to me that my work engage in a deep dialogue with the public—first visually, and then, from that starting point, to show them something they have never seen before, in the service of better understanding and, I hope, greater participation in the conversation we need to have about the state of global ecology.